Upholding Equitable Prosperity: Bridging the Social Security Divide for India’s Workforce

Context:

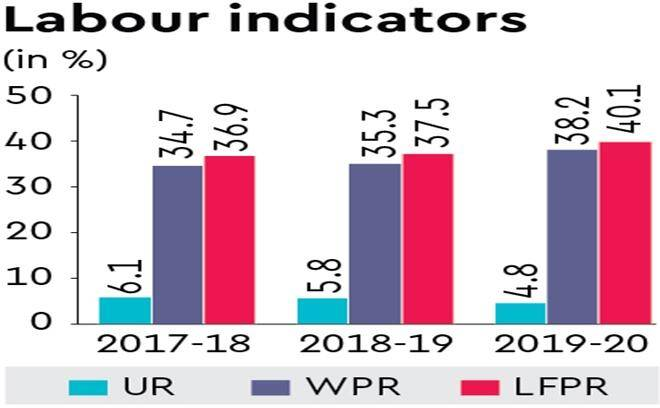

According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey Annual Report 2021-22, around 53% of all of the salaried workforce does not have any social security benefits in India. India needs to aspire to provide social security to all of its workforce, in a manner that is fiscally and administratively feasible.

Relevance:

GS – 02 (Government Policies & Interventions)

Prelims:

- Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana

- Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana

- Gig Workers

- Code on Social Security in 2020

Mains Question:

- Discuss the prevailing deficiencies in India’s social security ecosystem, particularly the lack of coverage for a significant proportion of its workforce and explore potential strategies for comprehensive reform. 250 words.

Dimensions of the Article:

- Neglected Social Security Landscape

- Underutilization and Dormant Schemes

- Comparative Global Approaches

- Unveiling India’s Vulnerable Informal Sector

- A Path Forward for India

- Reforming and Expanding

- Challenges in Implementation

- Empowering Marginalized Workers

- Strengthening Existing Frameworks

- Raising Awareness and Solidarity

Neglected Social Security Landscape:

- India’s policymakers have, by and large, not prioritized the imperative of establishing robust social security measures. Although policies are frequently announced, their practical implementation has been marked by limited budget allocations and minimal utilization.

- A glaring example is the National Social Security Fund, initiated in FY11 for unorganized sector workers. However, the initial allocation of a mere ₹1,000 crore fell dramatically short of the estimated requirement of over ₹22,841 crore, as projected by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability.

Underutilization and Dormant Schemes:

- An audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) in FY17 exposed that ₹1,927 crore, the accumulated amount since inception, had languished without being put to effective use. This mismanagement has rendered certain social security schemes ineffective.

- The National Social Assistance Programme, established in the 1990s to extend support to impoverished individuals lacking capable earners in their households, demonstrated a similar plight.

- Over time, the Centre’s contribution to old-age pension schemes stagnated at ₹200 monthly since 2006, falling below the daily minimum wage. In a more recent instance, the CAG found that the funds collected for social security provision to construction workers in Delhi saw abysmal utilization—merely 6% of the collected funds were utilized.

- Such instances reflect the vulnerability of select social security initiatives. Meanwhile, budget reductions continue to afflict the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

Comparative Global Approaches:

- Exploring international models, Brazil’s General Social Security Scheme emerges as an illustrative example. Rooted in contributions, it encompasses a spectrum of scenarios resulting in income loss for workers and their families, such as work-related accidents, disabilities, death, illnesses, family responsibilities, and unemployment.

- Even income loss due to imprisonment is covered for low-income insured individuals. Brazil’s comprehensive coverage extends to unemployment insurance and healthcare under the Unified Health System, with provisions for National Treasury intervention in cases of funding shortages. Simplicity characterizes the process of availing social security benefits, requiring no cumbersome document submission.

Unveiling India’s Vulnerable Informal Sector:

- Alarmingly, approximately 91% of India’s labor force operates within the informal sector, devoid of social security coverage.

- In the forthcoming two decades, as India transitions into an aging society, these workers, burdened with limited savings, face a glaring absence of adequate social protection. Despite the enactment of the Code on Social Security in 2020, which aimed to amalgamate existing social security regulations, it largely concentrated on formal enterprises, neglecting the informal sector.

A Path Forward for India:

- Charting a path toward comprehensive social security in India entails adhering to fiscal and administrative feasibility. Three fundamental principles emerge:

- First, an extension of employer and employee contributions within the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) framework for formal workers.

- Second, for informal workers with substantial earnings, a system of partial contributions could be introduced, coupled with encouraging informal enterprises to formalize and augment contributions.

- Third, the government should intervene for individuals who are unemployed, have discontinued work searches, or earn insufficiently.

- The estimated cost of extending social protection to the poorest 20% of the workforce amounts to ₹1.37 trillion, equivalent to approximately 0.69% of FY20 GDP.

Reforming and Expanding:

- While strides have been taken, more proactive measures are necessary. The introduction of the Code on Social Security in 2020 is commendable, addressing statutory frameworks for various segments, including urban and rural poor, gig industry, and informal sector workers.

- This code proposed a gamut of benefits, ranging from life insurance and disability insurance to maternity and health care.

- Efforts to digitize under the e-Shram platform have resulted in approximately 300 million workers enrolling and broader coverage for accident and disability insurance.

Challenges in Implementation:

- Placing the onus of registration on informal workers under the e-Shram platform overlooks the potential contribution of their employers, even if temporary.

- Inclusion of employers would facilitate formalizing employee-employer relationships. Broader scope could have compelled informal employers to make social security provisions mandatory rather than voluntary.

Empowering Marginalized Workers:

- Addressing the unique vulnerabilities of domestic workers, primarily women, demands special attention. Ensuring expanded coverage of social services, such as childcare, could offer much-needed support.

- Migrant workers, who often encounter discrimination and suspicion, would also benefit from enhanced social service accessibility. The organization of domestic workers across Indian cities warrants emphasis.

Strengthening Existing Frameworks:

- Strengthening existing frameworks, including the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), Employees’ State Insurance Scheme (ESI), and the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP), requires enhanced budgetary support and broader coverage.

- Administrative streamlining holds promise, including tackling the complexity of the social security framework for unorganized workers, which currently presents overlapping jurisdictions between State and Centre and ambiguous categorizations.

Raising Awareness and Solidarity:

- Uplifting awareness around social security’s significance remains vital to ensure maximum worker engagement.

- Collaborating with organizations such as the Self-Employed Women’s Association, running Shakti Kendras or worker facilitation centers, can enable impactful campaigns, especially targeting women, to disseminate information about social security rights and government provisions.

Conclusion:

The time has arrived for India to step beyond fragmented social security endeavors and sculpt an all-encompassing safety net that safeguards its diverse workforce. Fostering an environment of economic growth intertwined with social security is the need of the hour, particularly in a rapidly evolving employment landscape. As the nation strives for growth and development, the assurance of comprehensive social security emerges as a bedrock for equitable prosperity and sustained well-being.